I was 8 when my sister, Nikki Allan, was murdered. Now we know who did it

Stacey Allan was eight years old when she woke to the sound of urgent adult conversation in the room next door.

Her sister, Nikki, seven, had gone missing the night before from their home in Wear Garth flats, a 1930s housing complex in Sunderland’s East End, next to the city’s once-busy docks.

Her cousin Andrea walked into the bedroom. “Nikki’s dead,” she said. It was October 1992 and Allan’s happy childhood ended then.

“I remember this feeling, like I had never felt so lonely in my whole entire life,” she remembers. “Nothing was ever the same after that moment.”

A murder investigation began which would be characterised by endless rumour and gossip, a collapsed trial, social media campaigns and serious questions over police competency until it finally led to a child killer being brought to justice earlier this month.

After three decades of living in the community using false identities, David Boyd, 55, was convicted of Nikki’s murder at Newcastle crown court, to cheers of joy from family members and gasps of relief from police officers and prosecutors. He had lured Nikki to a derelict warehouse in the docklands, 300 yards from her home, beat her with a brick about the head and stabbed her in the chest and abdomen 37 times, before hiding her body in the basement.

For 30 years Allan has kept her counsel about what to the public was a notorious murder but to her was the devastating loss of her little sister. Her mother turned to alcohol and has admitted that Allan and her other sisters “have grown up knowing a mother who couldn’t get over the death of their sister and who was drinking herself to death”.

Stacey Allan leaves Newcastle crown court after David Boyd was convicted of Nikki’s murder. She has spoken for the first time of the agony that was inflicted on their family

NORTH NEWS AND PICTURES

Today, ahead of Boyd’s sentencing on Tuesday, Allan breaks her silence to tell of her own battles with addiction, how she doesn’t blame her mother, and how the murder conviction is “only the start” of them finding out the truth.

Allan names the men she believes were in the derelict building when Nikki was murdered. One is Steven Grieveson, the Sunderland Strangler, who is serving four life sentences for murdering four teenage boys. “We won’t give in,” Allan says. “I’ll keep going until the police have caught the rest of those men, because I don’t believe it was Boyd on his own who killed Nikki. And neither does my mam.”

A great place to grow up

In the early 1990s Wear Garth flats was a rundown, multi-level tenement complex with long balconies where people hung their washing, smoked and socialised. For the Allan girls, it was a great place to grow up. Raised by their single mother, Sharon Henderson, aged 26 at the time, they shared the apartment with their two other sisters, Niomi and Zara.

“It was a lovely place to be,” Allan says. “Everybody stuck together back then. We were tough kids, like proper paupers. We didn’t have much, but we had each other. And we were loved. I will always remember how much mam loved us.”

There was one year separating her and Nikki, and the two were extremely close: “We were like little boys, really, climbing trees, getting up to mischief. We would get wooden boards from the workmen and slide them down this long flight of stairs by the flats. We would have the best fun ever just going up and down those stairs. The whole community was together and felt safe. Everybody knew each other.”

The girls attended nearby St John and St Patrick’s Church Primary School, enjoying their lessons and making daisy chains in the break time. “Nikki was a right little character,” says Allan. “She was quite shy, but if she knew you, she became like a stand-up comedian. She would always be dancing and doing gymnastics. What a lovely little girl, honestly.”

At night, Nikki would climb into her bed with her older sister, even though they had separate bedrooms, sleeping against her back for comfort.

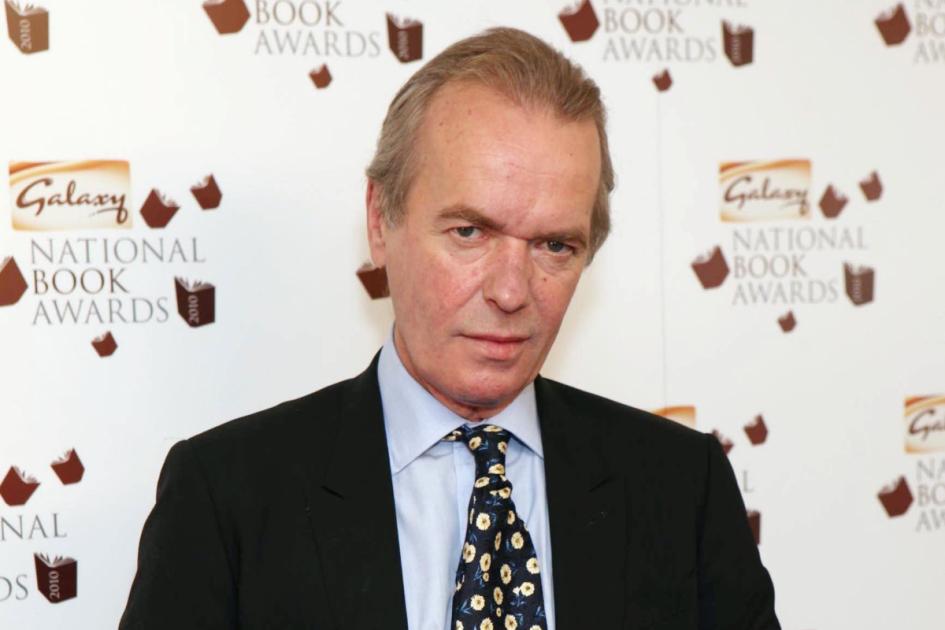

In the frame: George Heron, left was acquitted, while Steven Grieveson, right, the Sunderland Strangler, was accused. Boyd, centre, who was found guilty, used fake names and was described as “creepy” by the children

Dave the beast

Allan remembers her sister’s killer moving into the Wear Garth flats three floors above them and a few doors down from her grandfather’s flat. Boyd was considered an oddball by the groups of children who played together in the housing complex. They called him “Dave the beast”.

Boyd, 25, who had a frizzy brown mullet and a thin moustache, and often wore grubby white vests covered in food stains, had moved in with his babysitter girlfriend. He was using the fake name David Smith, and sometimes David Bell.

In 1986 he was convicted of causing a breach of the peace by approaching a group of children aged between eight and ten in Sacriston, Co Durham. He seized a girl by the arm and asked her for a kiss, warning her not to say anything. He had a second conviction from the same year for indecent exposure to a female jogger.

“I can remember him loads,” Allan says. “He was always on the veranda, looking down at the kids playing in the courtyard . . . I always got a creepy feeling from him.” Also hanging around was Grieveson, with a group of men sniffing glue in the derelict Quayside Exchange building where Nikki’s body was found.

Nikki vanishes

On October 7, 1992, Nikki went with her mother to visit her grandfather. At 8.30pm she left alone to walk 150 yards down the stairwell and across a short corridor to her own flat. When Henderson came home ten minutes later, Nikki had already vanished.

“I remember being in bed and mam shaking me,” Allan says. “Where’s Nikki? Where’s Nikki?” I told her, ‘I don’t know.’ Then I remember loads of people in the flat, and mam being so worried. It freaked me out. I went to my granddad’s flat and slept in one of the bunkbeds in the back bedroom, out of the way. I didn’t think she would be hurt. I literally didn’t know bad people like that existed back then.”

A search that evening involved 100 police officers and local people. Nikki’s shoes were discovered neatly placed outside the Quayside Exchange building. A neighbour found her body in the basement, and a passer-by reported hearing a child’s screams coming from the building the night before.

“The next morning I woke up at my granddad’s,” Allan says. “I remember hearing lots of people talking about Nikki in the room next door. Then my cousin, Andrea, came in. She was only nine years old — a year older than me.

“Me, Nikki and Andrea were all really, really close. Andrea told me: ‘Nikki’s dead.’ I couldn’t believe it. It was like my brain shut down after that. From that day on I never went back to school.”

Hurtful lies began to circulate that Nikki had been neglected by her family, and left to walk the streets alone the night she went missing. Another suggested she had been begging outside a pub.

Henderson once said: “When the child of a single mother is murdered, it’s as if they weren’t looked after properly and that we let them run wild. But I would die for any of my bairns.” Weeks after the murder, a local man, George Heron, 24, was brought in for questioning by police. Police found a blade in his flat which seemed to match the wounds on Nikki’s body. After three days of questioning, and 120 denials that he had killed her, Heron confessed.

His trial in Leeds in 1993 saw scores of people from Sunderland’s East End travel to court each day but the judge ruled police interviews were inadmissible due to police officers using “oppressive methods” and directed the jury to deliver a “not guilty” verdict. Fighting broke out in the court and jurors were in tears.

In 1994, Henderson sued Heron for damages for “battery of a child resulting in her death”. He did not contest and she was awarded more than £7,000 she has never received. Earlier this month, Northumbria police publicly apologised to Heron, who is expected to read a victim impact statement on Tuesday.

Meanwhile, Boyd vanished from the Wear Garth flats. The day Nikki’s body was found, he left the housing estate, says Allan. Seven years later, he was convicted of indecently assaulting a nine-year-old girl in a Teesside park. He later told his probation officer he had sexual fantasies about “young girls”, yet still police did not investigate him over Nikki’s death.

Numbing the pain

In the years that followed the murder, Henderson struggled to cope and has made no secret of her battles with alcohol, triggered by grief.

For Allan, it was tough. “I love my mam,” she says. “I mean, she’s been there for me my whole life and I feel so sorry for her. I think she saw Nikki in me. We were like identical twins. We used to wear matching clothes and everything. Mam obviously turned to drink and my childhood hasn’t always been easy, but you can’t blame her.”

As a teenager, Allan would live between her mother and other relatives. She was unable to hold down a job, and used boxing and drugs to numb the pain of her loss. In her twenties, she moved to Middlesbrough.

“I went on a rampage,” she says. “I went to raves and parties and took recreational party drugs as a coping mechanism. I was lost, really.”

Despite her own struggles, Henderson turned detective, drawing up a list of suspects who lived in each flat in the complex, ruling them in or out of her investigations. She whittled down the names until there was just one left: Boyd. In 2016, she met Steve Ashman, then the chief constable of Northumbria police, and pleaded with him to reopen the case.

A cold case team was set up and Boyd was tracked down to a flat in Stockton-on-Tees. For years he had lived under assumed names. New forensic tests had found his genes were a match for microscopic samples found on two items of Nikki’s clothing. The DNA was on the waistband of her cycling shorts and under the armpits of her T-shirt, helping to deliver the successful conviction.

The family believe this is the beginning of finding out the truth, rather than the end. “I think mam has been right about everything from the very start,” Allan says. “I think there’s more men who were involved that night. There are others out there involved in Nikki’s murder. And we won’t rest until the police have caught each and every last one of them.”

A Northumbria police spokesman said: “Following an incredibly complex and thorough investigation, we are absolutely satisfied that David Boyd is the only person responsible for causing the death of Nikki Allan.”

Living for Nikki

Five years ago Allan made a conscious decision not to die like her sister.

“I woke up one day and thought ‘I can’t do this any more.’ One of my problems was that I was so independent. Whenever I had people reaching out to me, I would just run away from it. Now I help people going through similar situations.”

She works for the charity Recovery Connections, which seeks to support all those affected by substance misuse. They helped her kick her recreational drug habit and party lifestyle, and gave her opportunities to train as a boxing coach. She is now qualified and teaches young people in a boxing gym, as well as working for the charity.

“It was always my dream to be a boxing coach,” says Allan, who has a son and two daughters of her own. “Now I’m living that dream, for me and for Nikki.”