Interview with author Claire McGlasson

IN HER new novel, The Misadventures of Margaret Finch, the author Claire McGlasson tells the story of a young woman who finds herself in Blackpool in the 1930s, a recruit of the relatively new Mass-Observation project. Her job was to work undercover, recording people’s conversations and behaviour, as part of a national scheme, which ran from 1937 until the mid-1960s, designed to build a picture of life in Britain.

In the story, Margaret encounters the Revd Harold Davidson, formerly Rector of Stiffkey, in Norfolk, who is down on his luck and trying to scratch a living through increasingly bizarre appearances as a showman. These culminate — catastrophically — in an extraordinary stunt involving the recreation of Daniel in the lions’ den.

Davidson, nicknamed “the prostitutes’ padre”, is, of course, a historical figure (1875-1937) who combined his parish duties with an enthusiastic ministry to women of “easy virtue” in Soho — and was unfrocked after a notorious public trial (Books, 29 December 2007).

His case was the subject of national scandal and speculation; views on his behaviour remain divided today. Was he unjustly accused, and innocent of wrongdoing, or an exploiter of the vulnerable? His epitaph at Stiffkey reads: “He was loved by the villagers who recognised his humanity and forgave him his transgressions.”

This is not the first novel to be written about Davidson; there have also been musicals, a play, and a film. What was it that caught Ms McGlasson’s interest?

She says that she came across the Stiffkey story in the course of her work for ITV News, for series, Hidden Histories. “When you’ve worked the same patch for many years, as I have, finding something that you’ve never heard of before can be quite challenging,” she says. At the time when she first encountered Davidson, she was working on another novel, but squirrelled the story away for future use.

Davidson’s story was extraordinary: an instance of the fact that is stranger than fiction. “I knew there was something there,” she says. It wasn’t until she went up to Blackpool — “a big part of my family history: the book is dedicated to my grandparents, who spent their summer holidays there” — and started going through the archives at the museum and reading about the sideshows that were such a feature of Blackpool summer holidays that the idea really took shape. “I came across Mass-Observation, which I’d heard about for its later work, and the diaries that people kept, but I had no idea of this sort of undercover operation and how it started,” she says.

THE premise of the novel is that Margaret stumbles across Davidson in the course of her research and begins employing her powers of observation in an attempt to discover the truth about him. “I didn’t want to write just about Davidson,” Ms McGlasson says. “I was more interested in the women around him.”

Why does the fictional Margaret become quite so fixated on Davidson? “I think he was very charismatic . . . and certainly his parishioners, from what I have read, loved him. I think he also takes an interest in her, in a way that she’s not used to.”

Margaret is drawn as a character “who desperately wants to believe in an absolute truth”, the author says. “She wants to [believe that] there’s a right and a wrong and a true and a false. And he’s a bit of an enigma to her. I think she also thinks that she can help him . . . He’s in quite a precarious position by the time he’s in Blackpool.”

So, does Ms McGlasson herself cast Davidson as villain or hero? “I want readers to make up their own minds,” she says. “I know what I think, but I don’t want to pre-empt that.” She hopes that readers will finish the book before turning to the internet (“the problem with writing about a real person from history”).

What is the appeal of blending fact and fiction? “I think that it comes largely from my work as a journalist, probably. For me, when I watch or read something, and it says ‘inspired by a true story’, I just find it much more interesting and compelling.”

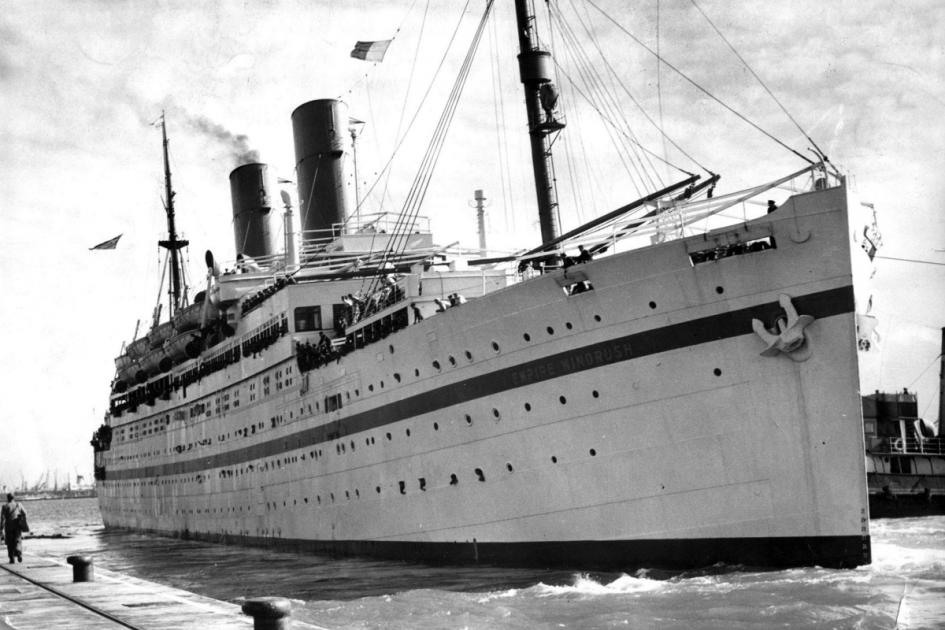

AlamyHarold Davidson at a pyjama party in his rectory, an undated photograph from before 1932

AlamyHarold Davidson at a pyjama party in his rectory, an undated photograph from before 1932

There is, however, an ethical challenge. “I think that when we’re writing about real people, we have to be comfortable with sitting within our own boundaries,” she says. “I wanted everything that I wrote to grow from something I’d read. . . I want it to grow from the truth.”

Ms McGlasson wrote the book during lockdown. “But some of the ideas grew from my reporting of Brexit,” she says. She was fired up by her observation that people from deprived areas of the of the country were dismissed during the Brexit debate.

“Their voices were silenced rather than engaged with,” she says. “Undoubtedly, in my view, there were some pretty hateful views expressed during Brexit, which I found personally objectionable. But I think the broad-brush dismissal of genuine concerns about funding of public services and so on left a silence which, ironically, allowed right-wing voices to be amplified.

“The ‘othering’ of groups of people based on class is something I feel very strongly about. Poverty does not necessarily equate to ignorance.”

This was reflected in the framing of the Mass-Observation project, which is explored in the novel. “Tom Harrisson, one of the founders, said he’d studied the cannibals of Borneo and now wanted to study the cannibals of Britain. . . There’s this idea that [working-class] people can be mocked or ignored.”

The best historical fiction holds a mirror up to the past, she says. “We think that class used to be a problem, but it’s still very prevalent; and we think that this obsession with celebrity and the cult of personality is [something we experience] only now; but if you look back at Davidson you realise that he was infamous. . . That’s where I was coming from.”

THIS book, The Misadventures of Margaret Finch, is Ms McGlasson’s second novel. Her first, The Rapture, was also inspired by history and has a religious theme. It tells the story of the Panacea Society, a group of women who moved to Bedford in the 1920s, believing that their leader, Octavia, was the Daughter of God and the Messiah (Features, 27 July 2011).

“Octavia” was, in fact, the widow of a vicar, and formerly known as Mabel Barltrop, who came to believe that she had the power to bring an end to the world’s suffering. Her followers began to flock to the town, buying neighbouring houses so that they could knock down garden walls to create a communal space, which, they claimed, was the site of the Garden of Eden.

The Panacea Society believed that women would bring salvation, after the loss of their husbands, brothers, and sons in the First World War. The route lay partly in a box sealed by the prophetess Joanna Southcott more than a century earlier; she had specified that it could be opened only at a gathering of the 24 bishops of the Church of England. (The bishops were not inclined to co-operate.)

“The women of the Panacea Society were infamous, just as Davidson was,” Ms McGlasson says. “They became the punchline of a joke. They were ridiculed, but they sought this publicity themselves, hiring billboards and printing pamphlets.”

It would be easy to ridicule the Society’s members, she says. “But I was much more interested in why they would be in that situation, and why they would stay in a situation like that, how that happens,” she says. “I don’t think the facts always tell the full story. It’s the gap between how someone sees their life and how everyone else might see it, that’s the sort of rich seam to be mined.”

In the 1930s, 70 members of the Society — almost without exception, highly respectable middle-class women — were reported to be living in Bedford. They lived together in the joyful expectation of the Lord’s coming — to the point of preparing a house for Jesus. The community had global reach, with more than 2000 members, and their healing ministry reached more than 130,000 people, by means of linen squares posted out on request.

Ms McGlasson mentions a 2003 documentary, which featured a member of the community explaining that the people currently renting the house had been warned that they might have to leave in a hurry, but not why. “I’m paraphrasing, but she says something like, ‘Well, of course, Christ’s will be a radiant body, but we’ve put an en suite in, just in case,’ and it’s wonderful.” The Society finally closed in 2012 when its final member died. (There remains a museum and a charitable trust.)

“I was interested in how the rules of the society changed as they went along,” she says. To begin with, no members were going to die. “Then Octavia died, and, with each step, these unthinkable things were sort of accommodated.”

In her novel, the story is told through the eyes of Dilys (a historical figure), whose faith comes under great threat when a new member joins the Society. An unravelling of sorts occurs — although the ending of the novel is a little ambiguous.

Why did the Society thrive? “The thing about a cult is that you don’t call it a cult when you’re in it,” she says. “There is nothing extreme or ridiculous about the Truth if you believe it. You might think, ‘That would never happen to me,’ but it does happen to people. What’s fascinating is to think, ‘How does one get to that place?’”

The Panacea Society emerged from the trauma of the First World War. “It’s probably also [to do with] the biggest question in Christianity, of how God can allow suffering.”

There was a need, she believes, to make sense of the terrible losses of the war. “I think that they desperately wanted to make sense of that, and make that into a positive,” she says. There was a sense that men had made “rather a mess of things” recently, and it was now up to women to bring healing.

Cults are much more frequently associated with men and power and sex, she says. “Octavia was such an unlikely cult leader. And I think, in some ways, perhaps a reluctant one. I’m not saying that she didn’t have very strong opinions and enjoy having things her way. But she’d suffered from mental ill health, and she was then told by her friends that there was a reason for this, and that she was carrying this burden to save people here on earth. I think that became an enormous burden to her.”

Ms McGlasson is interested in the mix of radical and conservative elements of the Society. “Certainly within the Church, the ideas are very radical. The idea that they believed in this sort of feminist interpretation of the Bible, and the Holy Trinity becoming a ‘quadrinity’, with the extra person of the Daughter of God.

“On the other hand, it was very conservative, with a small ‘c’. A lot of it was about holding on to this way of life, this obsession with the way things are done, like using the correct knife. I think was was probably a symptom of wanting to hold on to the way that things were, with this fear of the future.”

DOES she recognise a common interest in religious themes in both novels? “I think I’m interested in thinking about the past through a contemporary perspective with the understanding we have now,” she says.

Today, we might use different terms for people’s experience: mental-health conditions, for example, that once were ascribed to religious feeling. She thinks that Octavia suffered from misophonia (a sensitivity to certain sounds that can trigger outbursts). “Then there are the sort of punishments that people would inflict on themselves in the name of devotion. I think it’s really interesting to look at those things now, in terms of eating disorders or self-harm. There’s that same need for control.

“I was really interested [when writing] The Rapture about the experience of feeling in a relationship with God, and the way that people describe that excitement. It could be confused with the feelings of romantic love. Today, we see the two things as being in opposition, but, when you read devotional writings from the medieval period, it is described as the same euphoria.”

Does faith play a part in her own life? No, she says. “I mean, I grew up going to Sunday school because it was happening in my village, and I dabbled a little with an Evangelical church in my teens. But [faith] is not something I have, but it’s something I’m fascinated by, and respectful of, I hope.

“I think that religion — and particularly Christianity, because it’s the religion of our nation — is open to ridicule and disrespect, in a way that I feel other things might not be. So I was very keen not to be disrespectful.”

Perhaps, she says, it is because she doesn’t have a personal faith that she finds it so fascinating. “But I don’t think that Margaret Finch is really a book about religion. I think it’s a book about faith in people, and our belief in absolute truth and the black-and-white of people’s views.”

What is she working on now? “I’ve spent a few days in a convent recently, as part of my research around themes for my next book.” She laughs. “This isn’t going to help with my claim that I don’t only write about religion.”

The Misadventures of Margaret Finch is published by Faber & Faber at £14.99 (Church Times Bookshop £13.49); 978-0-571-36372-8. The Rapture is published by Faber & Faber at £8.99 (Church Times Bookshop £8.09); 978-0-571-34519-9.

From the Church Times archive: ‘My innocent grandfather’ (6 July 2007).

From the Church Times of 15 July 1932: His conduct was, to say the least, throughout foolish and eccentric. Yet there can be no doubt that he was originally moved by a high Christian impulse, and that he is still regarded by many as a champion of the outcast and the wretched.

However necessary the proceedings may have been, the spirit in which they were conducted has shocked the public conscience. The secret inquiry agents, the characters of some of the unnecessary witnesses, above all, the photograph, made the trial both undignified and unChristian.

We are reluctant to criticize Chancellor North, who, owing to the way in which the case was placed before him, was faced with a number of questions of fact which, unlike an ordinary criminal judge, he could not leave to a jury, but had to decide himself. . . [But] A word of real sympathy by the Judge for the ideal which, at least in the beginning of his career, Mr. Davidson had set before himself, would have raised the Church in the opinion of the masses.